Aliyah: A Journal

(Yes, Seriously)

Monday, April 28, 2025

Chometz Brie!

I didn't want to throw away Little Girl's crusts from her last 3 batches of sandwiches. I didn't make any matza brie this Pesach. I didn't take the foil off of the stove top yet. Do you see where these simple sentences are going?

And FF made French toast for his lunch for tomorrow, as long as I was cooking "crust brie."

Monday, April 21, 2025

Proud

I typically walk BY to kindergarten every morning. He rides his balance bike, and I push the stroller (and wear a baby carrier). At certain parts of our walk, cars are allowed to park on the sidewalk. Since BY on his balance bike is narrower than me pushing a stroller, he can often pass cars on the sidewalk, while I am forced into the street.

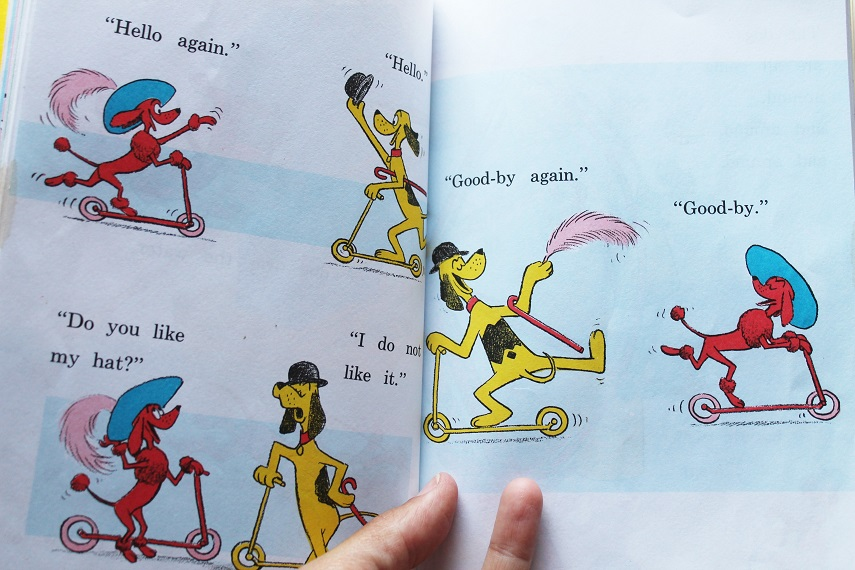

A few days ago, there were a few cars in a row where this happened. As the first car separated us, we called a cheerful, "Goodbye!" followed by a "Hello!" a few seconds later as we emerged from next to the car. At the next car, we again wished each other goodbye and then, "Hello again!" I was about to respond with a terribly witty quote from Go Dog Go, but BY beat me to the punch: "Do you like my hat?" he asked.

We laughed and laughed. I am very proud.

OMG

I have previously mentioned that The Newest Kiddo (TNK) was born quickly. I was already grateful that we made it to the hospital. (Looking back, I realize that I must have finished transition in order to say without shrieking or screaming, but only with absolute definitude: "Oh, no. I am NOT having this baby in this car.") However, I didn't realize just how lucky I was.

I am now filling out an eCRBA application for TNK. This is essentially an online US birth certificate application, and the response options for the first question stopped me in my tracks:

Tuesday, March 25, 2025

Hi There!

Baruch Hashem, I gave birth to a healthy girl just over a month ago. As everyone kept blessing me, she was born quickly and easily and healthily. She was even born in the hospital, but just barely.

**

About a week before I gave birth, Husbinator, BSM (11), and BY (5) went away for Shabbos to attend our good friends' oldest son's bar mitzva. I stayed home with FF (8) and Curly Girly (20 months). (Did I give her an internet nickname?) BSM came back having learned something about Life and about Himself, and which demonstrates beyond a shadow of a doubt that he is growing up: it is more fun to throw candy at the Bar Mitzva boy than to collect the candy that has been thrown.

**

I now know why Ema always describes me and Sister as being 20 months apart, as opposed to almost two years apart. I, too, was blessed with a 20-month-old and a newborn. That is not the same thing as an almost-two-year-old and a newborn.

**

This is also the first time I've had three kids under 6 years old: my older kids are spaced a little further apart. It is different. I am doing my best to be patient with myself and see what works. Between the flu (first a full-on case for the 20-month-old that I didn't manage to vaccinate, then a mild case for vaccinated me), Purim preparation, looking for daycare for next year, and Pesach preparation (in that order), I can't pretend that I'm not stressed, but overall, I think I am indeed being fairly patient with myself and open to figuring out what works.

**

Will blog more some other time.

Tuesday, February 25, 2025

The Weirdest Feeling

I just got a text message from Bituach Leumi (National Insurance, similar to the Social Security office, but they do much more), and... and... I said "Oh!" and my eyes genuinely teared up, and my heart was filled with... with... gratitude? Because of a communication from the most complicated government office I have yet to wrestle with???

Translation:

Hello,

The National Insurance wants to make it easier for you during this period and check if it's possible to automatically deposit maternity pay to your account, without you having to file a claim.

To this end, we request your permission to contact your employer to send us a Form 100 (details of your monthly salary), and we will handle this for you while you are on maternity leave.

Your approval can be obtained through the following link:

Please note: Alternatively, you can contact your employer independently, and request that Form 100 be sent to us.

Regards,

National Insurance

Yes. Yes, I very much would like maternity pay without having to find and fill out the 8-screen form and 16 bajoodle uploads of missing mystery documents, each in the correct format and size. Yes. Yes, yes, yes. Thank you.

Monday, October 7, 2024

It is October 7th

It's been a year. Well, a secular year, but how am I supposed to mark a year to the day on Simchat Torah? Many many many events today, in-person and virtual. I don't know details for any of the events, because I'm not going. Because. Because.

But a week ago, I got a link to a new song from Koolulam, a group that I like, and I ended up watching the video in the bomb shelter with the kids during the recent Iran rockets. And it's exactly the sort of song I expected from Koolulam: poignant and uplifting and all that stuff, and it breaks my heart anyway.

So I watched it again today. Because.

Lyrics are at this link, and here's a translation:

"Start From the Beginning" (Original Naomi Shemer Title: "The Party is Over")

And sometimes

The celebration ends:

Lights out.

The trumpet says

Goodbye to the violins.

The middle watch meets the third--

Get up tomorrow morning and start from the beginning.

Get up tomorrow morning with a new song in your heart.

Sing it strong, sing it in pain.

Hear flutes in the free breeze,

And start from the beginning.

From the beginning,

Always create your world in the morning:

The earth, the grass and all of the lights.

Then from the dust, in the image of people--

Get up tomorrow morning and start from the beginning.

Get up tomorrow morning...

Also for you,

The celebration ends.

And at midnight,

The way home

Is hard for you to find.

From the darkness we ask,

Get up tomorrow morning and start from the beginning.

Get up tomorrow morning...

Monday, September 23, 2024

Dichotomy

Honestly? I kind of want a war with Lebanon. The current situation is not tenable.

But during one of my meetings today, someone stepped out to take a call from the reserves. When he came back, I asked if he was staying or leaving. He said he just got called up. My unfiltered reaction? "Dammit."

I do want a war. I just don't want any Israelis to have to fight in it.

Sunday, August 18, 2024

Gateway Book

I recently brought home a free copy of Matilda (in Hebrew) for BSM, who enjoyed reading Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (also in Hebrew) a few months ago. I'd rather convince him to read Matilda in English, but I figure that reading in any language is a good thing, and anyway his Language Arts teacher told us the boy should read more novels. Having twisted my arm, I brought Matilda home, and BSM giggled his way through it, stopping periodically to tell me and Husbinator what was going on in the book, and how great it was.

BSM finished Matilda on Shabbos morning, with a huge smile on his face. So I told him the library has more books (also in Hebrew) by the same author. I further told BSM that we also have more books (in English) by the same author, including some books that the library probably doesn't have translated copies of.

I figured that was that, but a few minutes later BSM asked exactly where these alleged more books could be found. Shortly thereafter, BSM was back at the couch with four Dahl books. He read James and the Giant Peach on Shabbos afternoon, and he's currently going strong through The Witches.

Little Drama

A few weeks ago, I woke up to the sound of something falling, followed by loud crying from Baby WW. I ran to her room, but had trouble opening the door. Eventually, I figured out that although Baby WW was definitely on the floor and was very close to the door, she was not what was making it hard to open the door.

Turns out she had escaped from her little crib (obviously), and knocked over a folded step ladder, which was now leaning against the door.

Within a minute of picking her up, Baby WW was smiling and ready to play. Her mood made it clear she'd been having a great time until she startled herself, and looking around the room made it clear that her main source of entertainment had been the garbage can. Ah, tissues.

So I brought Baby WW to Husbinator (assembling this crib is one of the very few DIY tasks that I'm more familiar with than Husbinator is), and I collected pieces of the big crib. Huge thank you to Husbinator for storing the crib components behind and above furniture on the second floor, instead of bringing them to the attic! Also thank you to BY for staying in bed after waking up as soon as I touched the first crib component next to his dresser. Why that boy was so chipper at 3 am I don't want to know.

Assembling the crib, including collecting parts, only took about half an hour, which I think is VERY impressive, given the hour and lack of preparation. Speaking of impressive, I only put in one crib piece the wrong way. Unfortunately, that required taking off three pieces to fix, but thus crumbles the cookie. Also, I forgot that the drop-side railing doesn't stay up reliably, which is why we always make sure that side of the crib touches a wall. Naturally, the day-bed next to the crib means there's no room to slide the crib toward the middle of the room and just turn it around, so I gave up.

Luckily, Husbinator came in around then and said No, we couldn't just leave the side down: Baby WW had just climbed out of a crib with a low side. Seeing my Look, Husbinator said of course we didn't have to disassemble and reassemble the whole crib: we'd lift it up and rotate it in the air, above the height of the adjacent. It worked. Everyone went back to sleep. Whew.

Tuesday, July 2, 2024

Music

Last summer (wow, almost a year ago now!) I did a lot of daytrips with BSM and FF (and Baby WW, but she hardly counted, except when she cried). Lots of daytrips meant lots of driving, and lots of driving meant lots of requests to listen to music in the car.

I have a very simple rule about the kids listening to anything while I'm around: if it irritates me, don't do it where I can hear it. You want kids' songs or stories that grate on me more than nails on a chalkboard? Put on headphones, or take it to another room.

This is all fine and dandy at home, but for the car, we obviously needed a Plan. I liked my Initial Plan for the car: we only listen to music on my phone that I like. Eventually, though, the boys started asking me to add music to my phone for upcoming car rides.

It turns out that the Boys' Plan (which is still in effect a year later) works very well: I get to screen the requested songs on my own time, and choose whether or not to add the songs to my phone. And I get an idea of what songs the boys are listening to, and I even get exposed to new stuff that I like (along with some stuff that I don't, but I like most of it).

One of the songs the boys taught me blows my mind every time I hear it. The song is called "Guardian of the Walls," ["שומר החומות"] and was written in 1977. It's the chorus that blows my mind:

כן, כן, מי חלם אז בכיתה

כשלמדנו לדקלם על חומותייך ירושלים

הפקדתי שומרים

שיום יגיע ואהיה אחד מהם...

Yes, yes, who dreamed back then in class

When we learned to recite, "On your walls, Jerusalem,

I stationed Guardians" [Isaiah, 62:6]

That the day would come and I would be one of them?

Here's the version of the song that I added to my playlist. For your viewing pleasure, the Border Police also has a nice recording of the song.

Checking the News

I just realized something, as I loaded The Hill yet again.

When I'm checking the news more than, say, twice a day, what I'm really doing is hitting refresh on HasTheLargeHadronColliderDestroyedTheWorldYet.Com (a delightful website that I've mentioned in a previous post).

No, the LHC has not destroyed the world yet. (To quote the above website: "NOPE.")

No, the world isn't qualitatively crazier than it was a few hours ago. Let it be.

Friday, June 21, 2024

Before the Bath

Me: BY, do you have to pee?

BY: I feel that.... Yes.

Me: Okay, go pee.

BY [in Hebrew]: Okay, I'm going to relieve myself (להתפנות), bye!

Tuesday, April 9, 2024

Another Goof

BY, brother of FF, saw q-tips.

"Oh look, to-picks!" he exclaimed.

"Q-tips. Q-tips," I corrected.

Many giggles from BY, who finally gasped out, "No! Bananas!"

Tuesday, March 19, 2024

Weather

It's pouring across Israel today, and it is a Mighty Rain. As in, any bits of you that aren't encased in rain gear are guaranteed to get soaked if you go outside.

When I spoke with my boss, who does a good bit of farming on the side, he made a comment that I found unexpectedly comforting.

This rainstorm. It's the malkosh [late rain]. As in:

"ונתתי מטר ארצכם בעתו יורה ומלקוש ואספת דגנך ותירשך ויצהרך"

["And I will provide the rain of your land in its time, early rain and late rain, and you will harvest your grain and your wine and your olive oil"]

from the second paragraph of Shema.

Monday, February 12, 2024

10 Years

On Shabbos, someone was asking for our kids' ages, and BSM said that he's more than 10 and a half. At which point, Husbinator pointed out that our 10-year Aliyah-Anniversary must be coming up.

He's right.

It's today.

Wow. Wow, wow, wow.

OK, though, but that's the English date. We have another week-and-a-half or so for the Hebrew date. Gotta plan some sort of falafel-fest or something!

10 years. Wow. Good for us!

Thursday, December 7, 2023

No Procrastination!

At FF and BSM's school, each class has an in-school birthday celebration for the kids born that month. The birthday kids bring in chips, juice and cheap party-favors, and presumably the class sings happy birthday or some-such.

(The other mother sent her husband to buy chips and one bottle of juice that night; Husbinator had bought party favors on sale not too long ago, knowing we'd need them eventually; and we even had a bottle of juice in the pantry.)

In FF's class, the teacher asked the parents waaaaay in the beginning of the year to also prepare a brief slideshow about the birthday boy. This is a lovely idea, and I supported it whole-heartedly. You see where this is going, I'm sure. Naturally, within days of the teacher's announcement, I had forgotten all about the slideshow.

Luckily, FF started nudging me to make a slideshow over a month before his birthday. I was slowly easing from maternity leave back to work, so I had the time.

The two of us sat down, planned what he wanted to include, and chose photos. I typed it up. FF animated, with help from BSM. This process took hours, over the course of a few days. I forgot about the slideshow again.

Then a mother from FF's class called me earlier this week. She told me that FF and her son are the only kids with birthdays this month, and her son's birthday was the next day. Would I mind terribly celebrating on such short notice? The teacher had told her it might be an imposition on me, because making a slideshow in one evening is a bit much to ask?

Well! Well, well, well! Kol HaKavod to FF for not procrastinating! I am still aglow with pride.

FF and I did a quick check of the slideshow, which he had very carefully left open on his computer for the past month. With FF's blessing, I deleted a some extra animations FF had experimented with and not taken out. I sent a link to the teacher, and we were ready!

Seriously. I am so, so proud of FF.

Wednesday, November 8, 2023

Noise Complaint

Well, this has been sitting in drafts for a while now.

A month ago, the Rehovot municipality published a letter from the mayor regarding the neighboring city of Nes Ziona.

Here's a translation of some of the letter:

"Last night at 9:35 pm, alarms were heard in Nes Ziona. These alarms are so loud that they can be heard clearly even in the inner neighborhoods of Rehovot, on streets which are not adjacent to Nes Ziona - such as Sha'areim and Oshiyot.

As a result, the residents of the city mistakenly believed that the alarm was within Rehovot and entered shelters - without need.

It is unnecessary to write at length about the importance of maintaining the peace of mind of the public, as much as possible, and not causing unnecessary anxiety.

This is not the first time that the residents of Rehovot thought that an alarm has sounded in the city, to the extent that they entered shelters.

We ask that you regulate the decibel level of the Nes Ziona sirens, such that they do not alarm the residents of Rehovot.

This will be a significant improvement for the residents of Rehovot, so as not to wear them out with alarms both of Nes Ziona and the true alarms of Rehovot.

Please address this matter as soon as possible."

Or, TL;DR

Knock, knock. Hey guys, seriously? Can you turn down the volume?

Sunday, November 5, 2023

Pesukim on My Mind

There's a pasuk in Amos I think about a good deal, not just recently. It makes me feel validated. The pausk is Amos 3:6, but here are pesukim 4 & 5, too, for context:

ד הֲיִשְׁאַג אַרְיֵה בַּיַּעַר, וְטֶרֶף אֵין לוֹ; הֲיִתֵּן כְּפִיר קוֹלוֹ מִמְּעֹנָתוֹ, בִּלְתִּי אִם-לָכָד.

ה הֲתִפֹּל צִפּוֹר עַל-פַּח הָאָרֶץ, וּמוֹקֵשׁ אֵין לָהּ; הֲיַעֲלֶה-פַּח, מִן-הָאֲדָמָה, וְלָכוֹד, לֹא יִלְכּוֹד.

ו אִם-יִתָּקַע שׁוֹפָר בְּעִיר, וְעָם לֹא יֶחֱרָדוּ; אִם-תִּהְיֶה רָעָה בְּעִיר, וַה' לֹא עָשָׂה.

ה הֲתִפֹּל צִפּוֹר עַל-פַּח הָאָרֶץ, וּמוֹקֵשׁ אֵין לָהּ; הֲיַעֲלֶה-פַּח, מִן-הָאֲדָמָה, וְלָכוֹד, לֹא יִלְכּוֹד.

ו אִם-יִתָּקַע שׁוֹפָר בְּעִיר, וְעָם לֹא יֶחֱרָדוּ; אִם-תִּהְיֶה רָעָה בְּעִיר, וַה' לֹא עָשָׂה.

4 Will a lion roar in the forest, when he has no prey? will a young lion cry out of his den, if he has taken nothing?5 Can a bird fall in a snare upon the earth, where there is no lure for it? does a snare spring up from the earth, and have taken nothing at all?6 Shall a shofar be sounded in the city, and the people not be afraid? shall evil befall a city, and the Lord has not done it?

My high school principal quoted that pasuk in the context of 9/11, and I think of it when I jump at sirens. When alarms go off in a city, the natural response is fear.

*

FF and I went to the park on Shabbos afternoon, and, as it so often does, our conversation turned to, "Wait, was that a siren?" (Spoiler alert: it was not. It was a motorcycle revving and turning way more than necessary.) When I laughingly told Husbinator about our conversation (happens all the time! to everyone!), he said, "Yeah, it's called trauma." Which got me thinking about that pasuk in Amos again.

*

But it also got me thinking about a pasuk from Yeshayahu, which is part of Musaf on Rosh Hashana. Yeshayahu 27:13 says:

יג וְהָיָה בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא יִתָּקַע בְּשׁוֹפָר גָּדוֹל וּבָאוּ הָאֹבְדִים בְּאֶרֶץ אַשּׁוּר וְהַנִּדָּחִים בְּאֶרֶץ מִצְרָיִם וְהִשְׁתַּחֲווּ לַה' בְּהַר הַקֹּדֶשׁ בִּירוּשָׁלִָם.

13 And it shall come to pass on that day, that a great shofar shall be blown, and they shall come, those who were lost in the land of Assyria, and the outcasts in the land of Egypt, and they shall worship the Lord in the holy mountain in Yerushalayim.

A shofar being sounded, this time to signal the final redemption. And I giggled to myself, thinking, "When the shofar blows to signal Mashiach, you just know my first thought is going to be, 'Hey, was that an air-raid siren?'"

Ah, black humor.

But then I had another thought. One of my teachers in seminary, Rav Beinish Ginsburg, has a shiur about the dual nature of Matza. On one hand, matza symbolizes slavery: this is the bread of affliction that our forefathers ate as slaves in the land of Egypt. On the other hand, matza symbolizes redemption: this matza that we eat, why do we eat it? Because our forefathers' bread did not have time to rise before G-d appeared and redeemed them.

The shiur is great: I encourage you to listen yourself. Or read it. Brownies are mentioned. But the point I want to emphasize is this: a core feature of the seder night is the slavery-redemption duality.

Imagine it, says Rav Ginsburg. It's redemption time. It's time to bake bread, finish packing, and leave. Suddenly, Egyptians are pounding on your door, screaming to get out get out get out, grab your matza and get out. For years, this was a terror of slavery: Egyptian masters pounding on your door, screaming to shove matza down your throat and get out.

And suddenly, here you are again, in the same exact dreaded situation. Egyptians. Pounding on your door. Coming for you, screaming to get out. You grab your matza and leave. Because you're free. Because it's over. Because you're safe now.

The core symbol of slavery has become the core symbol of redemption.

Our narrative gets turned around.

We had been afraid, and our very fear becomes our freedom.

It could just happen the same way with our city-wide alarms.

Sunday, October 29, 2023

Little Doom-and-Gloom Break

Here's a post I thought about writing over Sukkot. Because I need a break from telling you stuff like BY loves the book Michal Asks Ima About Sirens, and his brothers enjoy listening when I read it to him. And that when I told Husbinator how much BY loves a kids' book about living with rockets, Husbinator said, "Good!" which is exactly how I felt, at least until I realized that I don't want my kid to totally connect to a book that explains what to do during real-life air-raids.

Right, so I won't tell you that. Instead, I'll talk about the water company.

Early one morning of Chol Hamoed Sukkot, while Husbinator was at shul, I got a text from the water company. "Hi there!" the text opened. "Is there any chance you have a leak somewhere? We noticed you're using an awful lot of water..."

"Hm," thought I. "I don't think we have a leak. I hope it's not our boiler in the attic spilling water everywhere... But that's the landlady's problem, so it's not a big deal, anyway. In any event, the attic is Husbinator's domain, as is the entire plumbing system, really. But I love him, and I know that message will stress him out. I don't really care, myself, but I'll have a look around after I finish my coffee. Man, I'm such a good wife."

So I finished my coffee and had a cursory poke around the house. Nothing. I wandered outside and checked what I was fairly certain was the water meter. Yeah, that dial was spinning pretty quickly. Not that I know how quickly it usually spins, but that spinning made me think I should actually investigate.

So I went through the house again. No water running that I could see.

I looked in the front yard. No water. I looked in the back yard. No running water. I looked behind the sukkah. And what do you think I saw? I saw a wet patch on the ground. Hm. That didn't look too bad, but what could have caused a singular wet patch between our storage tent and the sukkah?

I looked into the storage tent and stepped inside. My foot went, "Squelch." I looked down and took another step. My foot went, "Splash." I found an irrigation pipe under a toy mat absolutely gushing water. I put down the gushing irrigation pipe. I left the tent. I found random valves under the kitchen window. I turned the valves until the water stopped.

I checked the water meter, whose dials were now absolutely still. I gave BY what-for. Husbinator came home, heard what had happened, and gave BY more well-deserved what-for. Then Husbinator secured the valves with zip-ties, because we know our son and we know just how far what-for goes with him.

As soon as business hours started, I got a phone call. "Hi there!" said the helpful lady. "I'm calling from the water company--"

I cut her off and thanked her for the automated text. She brushed off my thanks and asked if we had taken care of the leak yet. "Yes," I assured her. "Well, actually," I backpedaled. "There was no leak. Our son made trouble. But we took care of it."

Now that's a useful service. I don't know if the water company here provides that service because they genuinely want to conserve water, or because we're entitled to a huge refund on our water bill if we present an invoice from a plumber for fixing a major leak. Regardless, I appreciate it.

Thursday, October 26, 2023

Just Weird

BSM had a friend over this afternoon. I don't know if the friend asked or if BSM offered, but within two minutes of the friend's arrival, BSM was showing him our bomb shelter. Weird times we live in.

BSM's tour was certainly best practices, but it brought to mind 4-year-old FF washing his hands with soap and water during Corona without anyone reminding him to do so.

Monday, October 23, 2023

Contests

Rehovot runs contests fairly often. Post a photo of your family's sukkah/independence day decorations/fun day at the new park, and be eligible to win something-or-another!

Well, today Rehovot invited residents to post a photo of our decorated safe rooms on the Rehovot Facebook page. Winner gets a free tablet!

Sunday, October 15, 2023

Routine

Luckily the boys decided to sleep in the bomb shelter again last night, and we let them, even though they are more apt to pull shenanigans in the shelter than in their rooms.

A bit after the last of the boys fell asleep, the red alert siren went off. Husbinator and I grabbed the baby and went to the shelter. A minute later we heard the standard muffled booms, and then we heard a BIG boom.

I checked my phone. Nothing on my local ladies' WhatsApp groups. Nothing on official Telegram channels. I checked again. Nothing. Nothing. Nothing.

Finally, a solid 3 - 4 minutes after the boom, my groups began the Same Exact Conversation we have every single time there's a siren.

(Actually, we skipped the "OMG sirens!" And " Why didn't I hear it?" "Why didn't my app go off?" stages. I think we haven't had that part of the conversation for a few days, now: maybe people are figuring it out?)

But sure enough, my chats filled up with the same pointless posts that go up every time:

Whoa, is everyone OK?

That was really loud.

Loud.

Yeah, crazy loud.

So loud!!!

Hit or interception?

Open area.

Whyyyyyy?

Where did it hit?

NO, DON'T SAY WHERE IT LANDED!

Who can I contact to install a shelter door?

I did not know that I craved the comfort of this routine. Yes, everyone thought it was loud. No, it's not just us. As inane as the conversation is, it is good to know that we are not alone.

Wednesday, October 11, 2023

Today I Feel...

I like the Hebrew much better, but here's the English:

Monday, October 9, 2023

Well.

I am not exactly in a headspace to write, but I want to write. So.

I didn't understand. When shul was so empty on Simchas Torah, I thought it was because people weren't comfortable walking all the way to shul, what with all the rockets in Rehovot between 6:00-9:30 am. But I was surprised by that decision. Turns out I was right to be surprised: people weren't absent due to the rockets. They weren't there because so many people had been called up to the army.

Auntie Em and Uncle En were here over Simchat Torah. (Mazel tov Dr. Wiggle Wumpus, and sorry it took us 4 months to get kiddush going for you!) At some point in the late morning/early afternoon, Auntie Em told me she may have misunderstood, but someone told her there were ground forces in the field. I didn't understand. Wow, the IDF went into Gaza? No, ground forces in Israel around Aza. An invasion by Hamas. I stayed very calm, because I didn't want to understand. Well, we'll check the news after chag, and we'll see. Nothing to do about it now, anyway.

At the community lunch after shul, the rav said it was OK that we had danced hakafot, and he compared this to other terrible years where Jews danced on Simchas Torah. I was confused. Of course it's OK! It's just rockets... I didn't understand.

After chag, Auntie Em was very, very upset. On the phone with her daughters, whose husbands had all been called up. Still, I managed not to understand. Even after skimming headlines, I wouldn't understand why she was so upset. But I didn't actually read the articles, not really, because I wasn't ready to understand. I was only ready to be pretend-devastated that there was no school tomorrow. Disappointing, that, but not really a surprise.

Yesterday. Sunday. I started to understand. I am in shock. I was and still am mainly focused on my kids. Kind of pretending it's COVID-time, where my responsibility is to keep the kids entertained and in line. My WhatsApp chats are so busy, so filled with people doing Chesed. I am overwhelmed. I donated some money, but I a confused.

Why are people collecting food and clothing and hygiene supplies for soldiers? Don't the soldiers have that? Doesn't the army supply basic necessities? I understand sending gift packages, but why are people making actual food, asking for underwear and toothpaste and flashlights and... what is going on? Is this for real? Or are people just needing to help, so they're... what? I don't understand. I read two articles, and now I don't want to understand again. Yes, it seems that basic supplies are actually needed, as the IDF hasn't yet ramped up enough to supply everyone they called up. I won't understand. I feel bad that I am not joining the wave of chesed, but I am overwhelmed. I will try to be good. I will try to be kinder to my family. I will daven.

I made a schedule for today, Monday. Things are better for me today, especially with the schedule. I haven't checked the news yet. I don't want to understand. Later. Maybe later I will join the massive wave of chesed, but maybe I'll just donate money and let other people do that, and play to my strengths. What are my strengths?

Is this too upsetting? Should I not post it?

Yes, it's upsetting. But honestly, it's not upsetting enough. I have small problems: my family is safe.

Yes, I am posting.

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

On Uniforms and Costumes

The boys' school is part of a... chain of schools? Is that what you call an organization that has a bunch of schools in a bunch of different cities? Anyway, FF's class went to Yerushalayim yesterday, for a chain-wide Chumash party for first-graders. Included in the program was an address by Rav Amar. Here's a picture of the Rav, taken at yesterday's event:

Last night, Husbinator mentioned to FF that Rav Amar wears special clothing because he is a former Rishon L'Tzion (Sefardi Chief Rabbi of Israel). FF responded matter-of-factly, "Oh, I thought he was dressed up as Rav Mordechai Eliyahu." For your reference, below is a photo of Rav Mordechai Eliyahu TZ"L, also a former Sefardi Chief Rabbi of Israel.

Sunday, May 21, 2023

Learning Something New

A while ago, Husbinator picked up a (free second-hand) halacha book he thought the kids would like, and the kids liked it so well that we ended up buying the entire set. The series is called פניני הלכה לילדים: it's a kids' version of פניני הלכה, a halachic series written for adults. (Here's a link to the English version for adults, available as physical copies for purchase or free online.) I like the books because they lay out halacha clearly and logically, with a clear explanation, and the kids say they like the amusing illustrations.

Both BSM and FF read the books for pleasure: BSM reads them himself, and FF with Husbinator. Or so I thought. I mean, I know that BSM has read the books more than once, and I know that FF has been consistently asking Husbinator to read him a few pages before bed, and they're on their second volume. HOWEVER. It turns out that FF has gone rogue.

You see, in the summer, Shabbos finishes so late that we often have one or more of the kids go to sleep while it's still light out, and to appease the child/ren, we let him make his own havdalah on Sunday morning. Well, two weeks ago, FF informed me that the free ride is over.

This time around, when I told FF it was bedtime, he complained. Naturally, his defense of choice was it not being fair that he'd miss havdalah. Full of confidence and years of experience, I calmly told FF that he'd make his own havdalah tomorrow morning, now go upstairs.

But FF threw me: he did not yell, he did not insist that he wasn't tired, he didn't even complain that he didn't want to be the first kid to go to sleep. Instead, he countered with making havdalah on Sunday is lame because... if you make havdalah on Sunday, you only use wine or grape juice, with no candle or spices.

Um?

Well, that certainly worked as a stalling tactic, as I stopped telling the boy to go to bed, and instead asked him to show me the source for that one. Because he didn't sound whiny, he sounded educated. And I have never heard of that one.

So FF did, in fact, go upstairs immediately, though he just as quickly came back down with this:

And I flipped through the book with FF until we got to this page:

Exactly as FF stated: sure, you can make havdalah after Saturday night, but if you make havdalah on Sunday through Tuesday, havdalah is a prayer over wine or grape juice only, with no fire-playing or spice-smelling. Well, I know better than to argue with a book that I trust, so I put FF to bed on my authority as a parent only, without trying to convince him that havdalah would be fine.

But still, after I put FF to bed, I pulled a copy mishna berurah. Yup, really straightforward.

And here are the Shulchan Aruch and Rema in readable text format:

שכח ולא הבדיל במוצאי שבת מבדיל עד סוף יום ג' וי"א שאינו מבדיל אלא כל יום ראשון ולא יותר ודוקא בפה"ג ומבדיל בין קודש לחול אבל על נר ובשמים אינו מברך אלא במוצאי שבת ויש מי שאומר דהא דקי"ל טעם מבדיל ה"מ היכא דהבדיל בליל מו"ש אבל אם לא הבדיל בלילה כיון שטעם שוב אינו מבדיל: הגה והעיקר כסברא הראשונה ומי שמתענה ג' ימים וג' לילות ישמע הבדלה מאחרים ואם אין אחרים אצלו יכול להבדיל בשבת מבעוד יום ולשתות ולקבל אח"כ התענית עליו. [ת"ה סי' קנ"ט] עיין סי' תקנ"ג:

With a bit of Mishna Berurah:

(יח) אבל על הנר וכו' - דברכת על האור משום דבמו"ש הוא זמן בריאתו ועל הבשמים נמי משום כדי להשיב נפש הכואבת ביציאת נשמה יתירה וכ"ז לא שייך ממו"ש ואילך [עו"ש]:

So FF taught me something.

Wednesday, May 17, 2023

Know Your Audience

Baruch Hashem, I'm pregnant, due in early June. This means that for months now, in addition to taking my daily Famotidine, I've been swigging Maalox as-needed. When I went to the US with just a carry-on recently, I brought 3 little TSA-friendly bottles with Maalox, and I also ordered a bottle of Gaviscon from Wal-Mart to wait for me at Ema and Abba's.

(I intend to blog about that trip eventually: for now, know that it was a 4-day trip of Just Me, with Husbinator home in Israel with the three boys. I came to the US to take the USPTO Bar Exam, which I passed.)

Speaking of Gaviscon, it is ickier than Maalox. Also speaking of Gaviscon, the Directions include a line that I do not remember seeing before. See the bottom-left of the below photo.

Yes, that's right: "dispense product only by spoon or other measuring device": it's like they know. I guess it's not just me and Grandpa who figured out that measuring cups are a waste of time, and this stuff calls for some straight-from-the-bottle drinking.

Monday, May 8, 2023

Shorashim

This post is from way back in March.

FF wanted to know what "וַיֵּבְךְּ" means, and he was not impressed with my translation of "and he cried." So I offered an alternative explanation of "וְהוּא בָּכָה," and FF was totally fine with that.

Being a little puzzled about why FF was happy to accept a modern Hebrew translation of the Biblical word, but not an English translation, I started to explain that in a shoresh [linguistic root of a word], the letters כּ and כ are interchangeable... Seeing his slightly blank look, I asked FF if he was at all familiar with the concept of shorashim. He was not.

So I gave FF a bunch of different forms of the word "cry," (he cried, they will cry, to cry, the act of crying, a cry...) and pointed out that all of those "crying" words have a ב or בּ and a כ or כּ in them, so we know those 2 letters are in the shoresh. Before I could get to the point, which is that if we see a word with those 2 letters in that order, that word is probably related to crying, BSM jumped in, saying he has a nice easy trick to figure out the shoresh of any word.

And with great aplomb, BSM told FF to just take the word in question and say "he did that word yesterday," and whatever pops out of FF's mouth when he does that trick will be the shoresh. Without waiting for a reaction, BSM continued that usually there will be three letters in the shoresh, but sometimes there will be four letters (e.g, גלגל), and sometimes there will be only two letters (e.g., רץ). And that's all there is to it! And FF was perfectly satisfied.

Whoa. So much for the non-native-Hebrew-speaker trick of taking a word and peeling off all of the prefix-, suffix-, and conjugation-specific letters to see what you're left with, and then adding back any letters that have a tendency fall off of shorashim (I'm looking at you, א, ה, ו, י, נ and anyone else I may have forgotten).

It reminds me of that time years ago and a city away that I asked my manager if the word משפחתון (playgroup) is masculine or feminine, and she very kindly taught me a Useful Trick. "Just take that word and say 'a big noun,'" she explained, "And whichever gender of 'big' you use is the gender of the noun!" I then had to explain to my manager that as someone who didn't learn the language as a child, the whole reason I'm asking for the noun's gender is that I want to know which gender of adjective to pick, and I have no way of magically forcing the correct gender of adjective to just instinctively pop out.

And all of this nerdy talk reminds me of a joke YC told me the other day:

איך מבחינים בין ציפור לציפורה?

הציפור רץ והציפורה רצה.

[How do you tell the difference between a male bird and a female bird?

The male bird runs (v., m., pres., sing.), and the female bird runs (v., f., pres., sing.).]

Granted, it's a nerdy joke, but it's funny!

A Poem

A week or two ago, Husbinator told me he had an epic battle with a massive cockroach in our bathroom. Last night, I sent him this--unfortunately true--first-person poem.

***

"After the Battle"

I really hope

that I left a gift for you

on the floor of the shower.

Cuz if I didn't, then I totally gassed our bathroom, and the roach still escaped.

In related news,

we could use a can

of stronger bug spray

in our bathroom.

***

For those more interested in facts than poetry, I rush to assure you that yes, Husbinator did indeed find the size L gift I left on the floor, along with a size S gift that I had no idea was even there to get caught in the cross-fire. He then bravely flushed the gifts, making me feel much better.

Also, yes, eventually I will post about the actually post-worthy stuff, like cute kid stories, and Observations on Israelis and Hebrew, and Pesach, and passing my USPTO licensing exam. But for now, the poem.

Monday, February 6, 2023

A Less Brilliant Misunderstanding

Again with FF. Again with a misunderstanding, but this time it was mine. Sometimes homework is just really tricky.

FF was rolling along with his Language Arts homework when he asked for help: he had no clue at all what to do with the third line of instructions on this page:

So I had a look at the assignment, mentally running a rough literal translation:

"Act according to the instructions.

We will color the blanket with light blue.

We will circle with a circle a shoe.

We will copy a baby that is small and pleasant to the correct spot."

WAIT, WHAT???? I was fairly certain that I had translated each word correctly, but clearly I was missing something, as that line of instructions made little to no sense. I figured I'd finish to see if anything became clear, but no, the last two lines of instructions were perfectly straightforward and clarified nothing:

"We will color the presents in yellow.

We will color the shoes with blue."

Within minutes, I had my answer: "לכתוב תינוק קטן וענוג בשורה שמעל התמונה" - "Write 'A Small and Pleasant Baby' on the line above the picture." Well now, that made sense!

I thanked the mother who answered me, and was gratified when an Israeli mother responded that she had also been confused. Sometimes, it seems, homework instructions are just poorly punctuated and unclear, even if you aren't an immigrant!

A Brilliant Misunderstanding

Nearly every Friday, the kids' teachers send a brief printout that has about a page of questions covering what they learned that week, to discuss with the kids during the Shabbos meals.

A few weeks ago, FF's questions were from the section of Parshas Toldos that they learned that week. Everything was going normally (FF was answering most questions correctly, being stumped by a few) until this happened:

Husbinator: What did Yaakov tell Esav he wanted for the lentil stew?

FF: His girl.

Me and Husbinator: Wait, what?????

FF: Esav's biggest girl.

Me: Um... I don't think I ever heard that one before... [Getting slightly derailed] Did Esav even have any kids at that point?

Husbinator: No??? What are you---? Look, let's check the answer on page. Whoa, oh my Gosh, does that really say?--

Me: No way.

Husbinator: Wait, no, never mind, it just says--

Me: OH!!!! [Laughing.] Wow, that's amazing. It says בכורה!!!!

Me again to FF: Wow, that's awesome. Yes, I never realized that. OK, so FF, בכורה has two meanings. You're totally right, בכורה can mean a biggest girl, but here, בכורה means being the oldest.

[Husbinator and I proceed to explain what first-born-hood means, still reeling from this brilliant misunderstanding.]

We had a parent-teacher conference the next day, and of course Husbinator told the teacher this story. A few words into the story, the teacher jumped in insisting, no way, I did NOT tell them that nu-uh, no way, he did not hear that from me... Until the teacher also had the epiphany and figured out how FF got there, laughed, and agreed that's awesome.

FF is so cool.

Wednesday, January 4, 2023

I Love My Nerdy Friends

Remember that post I had a few months ago about iodized salt?

Well, it's not just one nerdy friend I have here, there are lots of nerds in this town. Here's a conversation from my local WhatsApp group for Park Moms.

So nerdy. So great.

Tuesday, December 20, 2022

Chanukah School

BSM and FF have school during Chanukah. Since the public school system is officially on Chanukah Break, they only have half-days, with Torah-subjects only.

BSM's rebbe sent the parents a message last night, asking us to send flashlights to school today. This morning, he sent us this photo (along with photos showing happy kiddies, but those are not for the internet):

This brilliant man ran class from inside a blanket fort today. Because it's Chanukah, so we learn Torah in caves, just like during the Chanukah era.

😜

A few weeks ago, I was holding BY, who, by-the-by, is now three years old and has a haircut. He is also, as you will presently see, following in FF's footsteps, and is clearly competing for the title of Family Goofball.

BY made some sort of noise, and I, being a bit of a goofball myself, told him, "Sh! BY is sleeping!"

BY laughed, raised his eyebrows, and said he was awake.

I said no, BY's eyes are closed, he is definitely sleeping.

BY raised eyebrows waaaaay up and said, "Nooooo, eyes open!"

I laughed and, taking pity on the kid, agreed with him that his eyes were opened, and he was, in fact, awake.

I looked down again a few seconds later, and BY's little fingerlach were desperately holding his right eyelid closed, as he attempted to keep his left eye open more than a slit.

I laughed.

BY proclaimed, "Look! Eyes open and closed!"

Tuesday, November 1, 2022

Immigration Day Wrap-Up (2021)

Speaking of Old Drafts, here's a draft from 2021 that just needed a tiny bit of polishing.

***

I ended up just sending BSM to school with his typical French Toast sandwich for lunch on Immigration Day. I come from America, I made you food similar to the food I ate in America, it is American food. Be done with this foolishness.

BSM came home from school on Immigration Day and said that he liked the kubaneh provided for the class by a Yemenite mother, which he said tasted like sweet challah. But BSM said he really liked the food provided by some mother whose family comes from Eastern Europe. BSM couldn't remember what it was called, but described the food as "Ashkenazi. It was like wrapped-up malawach with leben inside. It was soooo yummy. And the leben was sweet!" Friends, it seems that this was the first time my he-doesn't-know-he's-Ashkenazi son ate blintzes.

More importantly, obviously, was the fact that Abba II went in and talked to the kids, who were interested in what he had to say. And BSM's face just lit up when he told me that Husbinator sat next to BSM during Abba II's talk.

The winning story of the day though, is a Family Reunion.

BSM's teacher told the class about how his grandfather moved to Russia, then got send to Siberia during WWII, after which he made his way to Iran, then walked through all of Iran, Iraq and Syria with his wife and daughter until they got to Israel.

Then the gym teacher happened to walk by, and BSM's teacher asked the gym teacher to share his family's immigration story. So the gym teacher told the class that his great-grandfather was sent to Siberia during WWII, and then eventually made his way to Iran, then walked through all of... Hang on, said BSM's teacher. What? The teachers compared notes. They compared names. They are cousins.

Yom HaAliya

I have a draft sitting in my blog that was written on the 10th of Nissan one year, the day set aside by the Israeli Government as Immigration Day, since the 10th of Nissan is the day that B'nei Yisrael finally crossed the Jordan River and entered Eretz Yisrael. I didn't post the draft then, because it is too important to me to say imperfectly, and the draft is far from perfect.

But today is Yom HaAliya again (I know someone who knows the guy responsible for moving Immigration Day from "a few days before Pesach" to "the week of Parshas Lech Lecha"), and looking at the draft again, I think that it is too important for me not to say at all, and at least the draft begins to say it.

So I'll say it now, and maybe some other year I'll say it more elegantly, more tactfully, more convincingly.

***

At some point after I made aliyah, I decided that I wouldn't be that Annoying Person who's always annoying her friends and family to join her cultish pyramid scheme in her extreme life choice. And eventually I stopped nudging some people about making aliya. And time passed, and I told myself, "Really, don't be that guy." And I pretty much stopped nudging more people. And I think it's been a good long while since I've nudged anyone to make aliyah. At least not if they didn't bring it up first.

But I still miss you.

So please, consider considering it. Is it possible for you to live in Israel? Short-term, if not long-term; in the future, if not now?

And hey, if you do come, come for theological reasons, so I don't have to feel guilty. But I'll be honest: I'm not asking for a Friend. I'm asking for me. Come home?

Thursday, October 27, 2022

Cultural Differences

There's a spice blend here called Hawaij, which is available in a soup-type and in a coffee-type.

(Oh! Speaking of which, Turkish coffee comes in three types of packaging here: red [regular], green [with cardammom], and other [decaf]. People are slightly evil.)

Years and years ago, I bought some hawaij for Coffee, because it smelled nice. Eventually, I started using it instead of sugar. Coffee with hawaij tastes good, similar to pumpkin spice coffee. This is not shocking, as Wikipedia lists possible ingredients of coffee-hawaij as aniseeds (licorice), fennel seeds (licorice), ginger, cardamom, cloves, and cinnamon . Wiki also says "Although it is primarily used in brewing coffee, it is also used in desserts [and] cakes." So yeah, clearly, this is the Middle-Eastern version of a pumpkin spice blend.

I am going through this stuff so slowly and I enjoy it so much that I donated half-a-container to the kitchen in my office. This way, I can drink my instant coffee with yummy spices, and other people can also enjoy the goodness.

However, it turns out that the only thing other people can enjoy is a giggle at my expense. Apparently, in Israel, Pumpkin-Spice coffee is not an autumnal beverage enjoyed mainly by women. Here, Hawaij-flavored coffee is strictly for old Yemenite men.

Whatever.

Wednesday, October 26, 2022

Israeli Humor

I've mentioned before that Israelis don't pun nearly as much as I expect.

What I forgot to point out, though, is that Israelis play with psukim, instead. Here's a WhatsApp message that we got from BSM's teacher this morning:

בוקר טוב!

א גזינטע ווינטער לכולם 🤗

ישנה תופעה מטרידה של שכחת סידורים כרונית בכיתה!

אבקש מההורים היקרים לוודא את קיומו של סידור בנם, ולשלחו אחר כבוד בתיקו, ויקויים בנו מקרא שכתוב ״שבו האובדים מארץ האשור והנדחים מארץ מצרים״…

תודה!

Which translates as:

Good Morning!

A Healthy Winter to everyone 🤗

There is a disturbing occurrence in the class of chronically forgetting siddurim!

I respectfully request that the parents verify the existence of their son's siddur, and send him another one in his backpack. May we experience the fulfillment of the verse, in which it is written "The lost will return from the land of Assyria and the outcasts from the land of Egypt"...

Thanks!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)